DominionSections

Browse Articles

- IndependentMedia.ca

- MostlyWater.org

- Seven Oaks

- BASICS Newsletter

- Siafu

- Briarpatch Magazine

- The Leveller

- Groundwire

- Redwire Magazine

- Canadian Dimension

- CKDU News Collective

- Common Ground

- Shunpiking Magazine

- The Real News

- Our Times

- À babord !

- Blackfly Magazine

- Guerilla News Network

- The Other Side

- The Sunday Independent

- Vive le Canada

- Elements

- ACTivist Magazine

- The Tyee

- TML Daily

- New Socialist

- Relay (Socialist Project)

- Socialist Worker

- Socialist Action

- Rabble.ca

- Straight Goods

- Alternatives Journal

- This Magazine

- Dialogue Magazine

- Orato

- Rebel Youth

- NB Media Co-op

Radio

Plunderphonics

May 27, 2004

Plunderphonics

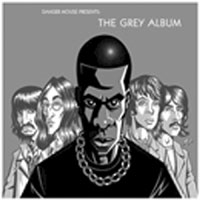

DJ Danger Mouse's Grey Album

Canadian artist John Oswald has made a career out of walking that line. He's been plundering sound archives since the early 1970s, when he began with the recorded works (and sanction) of William S. Burroughs. But Oswald specifies that it must be "blatant ... There's a lot of samplepocketing, parroting, plagiarism and tune thievery going on these days which is not what we're doing." Instead, Oswald plays with "transformed but still recognizable" audio quotations, delighting in their interaction.

Consider the same situation in print. If I wanted to write a book out of a thousand or so fused quotations, as Oswald's Plexure album is made with audioclips, I would put in a big fat bibliography or more footnotes than T.S. Eliot. Readable? Not so much; but legal? Certainly. In sound art, however, Oswald points out that creating such a "scholarly version" of Plexure would require negotiating "over a thousand clearances, and any one that is not obtainable would compromise the project." Is there no other way to create an audio footnote or sidestep sonic quotation marks?

Copyright showed up in the original American constitution, derived from England's 1709 Statute of Anne: for the encouragement of learning. The American exhibit Illegal Art points out the irony that copyright was "originally intended to facilitate the exchange of ideas, but is now being used to stifle it." Indeed, "if the current copyright laws had been in effect back in the day, whole genres such as collage, hiphop, and Pop Art might have never have existed." Canonical greats like Bach or Shakespeare would also have some answering to do.

Importantly, copyright is a commodity. Its tradability means that it is always the copyright holders, who may or may not be the artists, whose rights are protected. Financial and creative protection for artists become just financial interest protection for copyright purchasers.

What is most valued here? The right to make money off your own work? The right to determine who else is making money off your work? The right to have maximum influence over interpretation of your work, or to stave off its subversion?

There are two debates here. One is the question of what requires protection--creative production or the money it can generate. The second is between different conceptions of art. As Martin Cloonan, chair of the anti-censorship group Freemuse and Head of the University of Glasgow's Department of Adult and Continuing Education recently wrote: "One [conception] sees creativity as essentially social in nature and thus asserts that the rights of the public (or collective) are paramount...[T]he public's right to knowledge, to access the thoughts and deeds of others, is highly prized."

That's the belief of media project the DBI, propagators of the No Copyright Seal. Arguing that intellectual property concepts can only restrict the flow of info and ideas, the Department of Behavioural Investigation offers the seal to ensure that what it stamps can't be copyrighted by anyone, ever.

On the other hand, you could see "creation as an individualistic act where the rights of the artist (as vested in the copyright holder) are paramount. Here the right of the original artist is held to be paramount."

Between those polarized versions of art are the vast grey areas in which we find Oswald or DJ Danger Mouse, mucking around in other people's art to create artifacts anew.

So say the plunderers. Could we get a comment from the plundered?

William S. Burroughs, Elektra and The Grateful Dead, for example, have respected or requested that Oswald use their work. For his 1999 "sonic archeology" project Disembodied Voice, rights were not just given but the plundering project was actually commissioned. In this case, Oswald used pianist Glenn Gould's acclaimed recordings of The Goldberg Variations. What he used though, was not the sound of the piano, but of Gould himself, inadvertently humming along. Oswald isolated, enhanced, and in some parts replicated Gould's unconscious vocals and The National Ballet of Canada then danced to the virtuoso's haunting hum instead of his familiar piano performance.

At the other extreme, though, is Oswald's 1990 album Plunderphonic, which the recording industry demanded be destroyed. Because most looted work is represented by record labels, it is difficult to find artist to artist dialogue on the subject, but it is clear in this case that the industry was acting on the request of plundered artist Michael Jackson. No doubt the album's cover, which morphed an image of Jackson's body with that of a naked white woman, caused some offence.

Artistic integrity is certainly up for debate, but it is unfortunate that it takes place mostly in the courts and through sharply worded letters of warning to sound artists. The grey areas of intellectual property law leave room for experimentation and redefinition but the atmosphere is discouraging and it takes a certain amount of audacity to break through.

Related articles:

By the same author:

Archived Site

The Dominion is a monthly paper published by an incipient network of independent journalists in Canada. It aims to provide accurate, critical coverage that is accountable to its readers and the subjects it tackles. Taking its name from Canada's official status as both a colony and a colonial force, the Dominion examines politics, culture and daily life with a view to understanding the exercise of power.