DominionSections

Browse Articles

- IndependentMedia.ca

- MostlyWater.org

- Seven Oaks

- BASICS Newsletter

- Siafu

- Briarpatch Magazine

- The Leveller

- Groundwire

- Redwire Magazine

- Canadian Dimension

- CKDU News Collective

- Common Ground

- Shunpiking Magazine

- The Real News

- Our Times

- À babord !

- Blackfly Magazine

- Guerilla News Network

- The Other Side

- The Sunday Independent

- Vive le Canada

- Elements

- ACTivist Magazine

- The Tyee

- TML Daily

- New Socialist

- Relay (Socialist Project)

- Socialist Worker

- Socialist Action

- Rabble.ca

- Straight Goods

- Alternatives Journal

- This Magazine

- Dialogue Magazine

- Orato

- Rebel Youth

- NB Media Co-op

Radio

Lessons for an Audience

February 3, 2004

Lessons for an Audience

Kazimi's Shooting Indians explores representations of authenticity

In Ali Kazimi's 1997 documentary Shooting Indians, a whole sequence of studying is going on. Kazimi studies Iroquois photographer Jeff Thomas, who is mining the century-old works of white photographer and filmmaker Edward Curtis. The three are transformed.

It took more than a decade to make this quietly ironic film, which got a rare public screening in Victoria, BC last night. Looking around the filled-to-capacity auditorium, it was obvious that a non-native audience is hungry for the dialogue that this film, and the native speakers who followed its screening, made posible.

Ali Kazimi and Jeff Thomas: "the two indians".

Thomas' photography, now his strategy for approaching alienation issues, began with doubt and hesitation, as captured in Kazimi's footage of Thomas returning with a camera to his childhood reserve near Buffalo, NY. Resident attitudes were formed by the history of anthropologists and ethnographers, the only people taking pictures of natives. "People came, took something, left, and never came back," he said. "Never an exchange."

It is just such photography for which Edward Curtis (1868-1952) is famous.

"Prolific" is an understatement when applied to Curtis' body of work. More than 40,000 photos, transcriptions of hundreds of stories, and wax-cylinder recordings of songs were taken of First Nations throughout southern and northwest North America. "Resented" and "discredited" are just as indequate in expressing most present-day attitudes to his collection. Hailed at the time as tokens of the "vanishing race," in the 1980s people spoke up about how severely his photos were staged, retouched, and essentially falsified.

But Kazimi calls Curtis "the shadow... with whom [Thomas] seems to have made an uneasy peace." After a decade of studying Curtis' photos (he even got a job at the National Gallery for access to their collection) Thomas explains that "I was uncomfortable with his work," but uncomfortable enough, crucially, "to find out why."

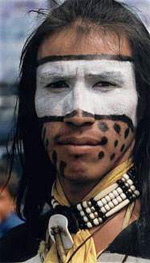

An untitled portrait by Jeff Thomas.

Along the same lines, to watch In the Land of the War Canoes as an exploitation of the culture it misrepresents is to deny that participating in it was, as Maggie Frank believes, an expression of choice. And market-tailored as the shooting was, Gloria Cranmore-Webster makes the point that Curtis' arrival in 1913,

And within Curtis' romance and retouching, between those absurd scenes staged for a white, city audience, Thomas found moving and empowering portraits. He went on to curate 150 such photographs into a show at the Ottawa Art Gallery. To cynics wondering how he could make this selection, Thomas offers an explanation that can guide the viewer through Thomas' own body of work. He explains that these pictures are much the same as any portraits of Toronto's aristocrats of the time. They are people dressing up for and looking into the camera. These are not stereotyped Indians, and to assume so (because of the rest of Curtis' work, and the time in which they were taken) is natural but misguided.

The error is in the search for authenticity. This was Curtis' mistaken reason for handing out cedar capes for his models to wear, instead of the bowler hats they were already walking down the street in. This is also the mistake of those who reject Curtis' artifacts today, and the school of thought he represents. It is what Thomas rejects by returning to Curtis' work. Because, as Thomas explained to Kazimi, "To look at my own history I don't think about Indianness." Far more personal insights of compassion and self-analysis arise instead.

For Kazimi, who began the project expecting to see totem poles on Thomas' NY reserve, what disappeared was the mythic Indian image he'd been taught. For Thomas, what appeared was the courage to demand nuance and a determination to return photography's focal point to its subject. And along the way they reinterpreted Curtis as a man whose mission changed from preserving historical curiosities to trying to protect living traditions. Taking a personal, reflective approach to the often-abstracted realities of aboriginal oppression, Shooting Indians practices the very message it carries.

Related articles:

By the same author:

Archived Site

The Dominion is a monthly paper published by an incipient network of independent journalists in Canada. It aims to provide accurate, critical coverage that is accountable to its readers and the subjects it tackles. Taking its name from Canada's official status as both a colony and a colonial force, the Dominion examines politics, culture and daily life with a view to understanding the exercise of power.