DominionSections

Browse Articles

- IndependentMedia.ca

- MostlyWater.org

- Seven Oaks

- BASICS Newsletter

- Siafu

- Briarpatch Magazine

- The Leveller

- Groundwire

- Redwire Magazine

- Canadian Dimension

- CKDU News Collective

- Common Ground

- Shunpiking Magazine

- The Real News

- Our Times

- À babord !

- Blackfly Magazine

- Guerilla News Network

- The Other Side

- The Sunday Independent

- Vive le Canada

- Elements

- ACTivist Magazine

- The Tyee

- TML Daily

- New Socialist

- Relay (Socialist Project)

- Socialist Worker

- Socialist Action

- Rabble.ca

- Straight Goods

- Alternatives Journal

- This Magazine

- Dialogue Magazine

- Orato

- Rebel Youth

- NB Media Co-op

Radio

Vioxx Populi?

November 6, 2004

Vioxx Populi?

Withdrawal raises questions about drug approval in Canada

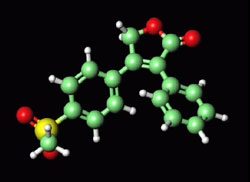

The molecular structure of Vioxx. The drug approval process for drugs like Vioxx in Canada is largely controlled by the pharmaceutical companies that develop them.

Since Merck's announcement, numerous class action suits have been launched against the company. The plaintiffs claim that Merck failed to adequately test the safety of the drug and warn physicians and pharmacists of the potential for adverse cardiovascular events. The case of Vioxx raises questions of how a drug with serious side effects made it to the market and stayed there for five years. More generally, it raises questions about the process of drug approval and consumer protection in this country.

In order for a drug to be approved, Health Canada requires data from animal or laboratory tests and from clinical trials. The clinical trials must "prove that the drug has potential therapeutic value that outweighs the risks associated with its use." Typically, clinical trials involve between 2000-3000 people and only investigate the effects of a drug for a short period of time. New drugs do not have to be tested against existing treatments – they only have to show that they are more effective than a sugar pill. And unlike the US, the data submitted to Health Canada is not available to the public, making it difficult for physicians and the public to evaluate a new drug. Some critics say that these policies enable pharmaceutical companies to produce and patent multiple and more expensive variations of the same drugs. These more expensive drugs are then marketed as new and improved treatments for the same conditions. Because the data is not public, and thanks to aggressive marketing campaigns, many doctors will prescribe the newer, more expensive medication without knowing whether it is more effective or not.

Most post-market research on pharmaceuticals is undertaken by the industry, generally to evaluate the effectiveness of the drug for other conditions, such as Merck's study of the usefulness of Vioxx in preventing colon polyps. This means that most studies do not get to be conducted by independent researchers who do not have a vested interest in a drug's approval.

Health Canada's Health Products and Food Branch reviews evidence of a drug's safety and effectiveness submitted to them by the manufacturer, and makes the decision as to whether or not the drug is acceptable for marketing. After a drug is approved, it is monitored through the voluntary submission of adverse drug reactions reports to the Canadian Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Program (CADRMP). Consumers or physicians can report drug reactions – but consumers are not aware of the program, and there are no incentives for physicians to file reports. However, companies are required to report any further findings of adverse reactions.

Within its first year of being on the market, CADRMP received 151 reports describing 417 suspected adverse reactions to Vioxx. Of these reports, 91 were classified as serious, including 5 deaths associated with Vioxx and 25 reports of suspected cardiovascular reactions. As reports are made to the CADRMP on a voluntary basis, they do not provide an indication of the prevalence of suspected drug reactions. As a result of a study conducted in 2000 in which patients taking Vioxx experienced an increased risk of heart attacks and stroke, Health Canada issued an advisory in 2002 stating that Vioxx should be used with caution in patients with a history of heart disease.

Concerns around the safety and marketing of pharmaceuticals are further fueled by proposed changes to Canada's Health Protection Act. Slated revisions include partial and full introduction of direct-to-consumer advertising. In the US, Merck spent $160.8 million (US) in 2000 advertising Vioxx to Americans, and made $1.5 billion (US) in sales. The US experience with direct-to-consumer advertising has driven up prescription drug costs, compromising public safety by encouraging the widespread use of drugs whose safety and side-effects are not well-known. While the Health Protection act currently forbids promotion of prescription drugs to the public via advertising, Health Canada has been extremely lax in enforcing the legislation since 2000. Direct-to-consumer advertising could mean that Canadians would be exposed to more prescription drugs, such as Vioxx, whose safety was uncertain.

As a recent editorial in the medical journal The Lancet observed, "[the] Vioxx story is one of blindly aggressive marketing by Merck mixed with repeated episodes of complacency by drug regulators." (The Lancet, October 7, 2004) Hopefully the example of Vioxx will be treated as an opportunity to re-evaluate slated revisions to Canada's Health Protection Act, and perhaps motivate efforts to increase the awareness of and incentives for adverse effects reporting, create a mandatory clinical trial registry that would force drug companies to report both negative and positive trial results, and enforce the prohibition of direct-to-consumer advertising. Because of Vioxx, Health Canada may have to convince the Canadian public that it is capable of serving the public's best interests.

» Canadian Health Coalition: Direct-to-Consumer Prescription Drug Advertising: Health Canada's Proposals for Legislative Change

» Women And Health Protection: Just say NO to direct-to-consumer-advertising of prescription drugs

Related articles:

By the same author:

Archived Site

The Dominion is a monthly paper published by an incipient network of independent journalists in Canada. It aims to provide accurate, critical coverage that is accountable to its readers and the subjects it tackles. Taking its name from Canada's official status as both a colony and a colonial force, the Dominion examines politics, culture and daily life with a view to understanding the exercise of power.