DominionSections

Browse Articles

- IndependentMedia.ca

- MostlyWater.org

- Seven Oaks

- BASICS Newsletter

- Siafu

- Briarpatch Magazine

- The Leveller

- Groundwire

- Redwire Magazine

- Canadian Dimension

- CKDU News Collective

- Common Ground

- Shunpiking Magazine

- The Real News

- Our Times

- À babord !

- Blackfly Magazine

- Guerilla News Network

- The Other Side

- The Sunday Independent

- Vive le Canada

- Elements

- ACTivist Magazine

- The Tyee

- TML Daily

- New Socialist

- Relay (Socialist Project)

- Socialist Worker

- Socialist Action

- Rabble.ca

- Straight Goods

- Alternatives Journal

- This Magazine

- Dialogue Magazine

- Orato

- Rebel Youth

- NB Media Co-op

Radio

How the Liberal Party Works

August 23, 2003

How the Liberal Party Works

We hold elections, but do our political parties practice democracy?

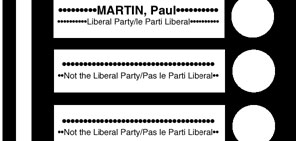

Is this what Canadian democracy looks like?

Why is everyone so sure that Paul Martin will win the leadership? Allan Rock and Brian Tobin, considered contenders early on, were so sure of a Martin victory that they dropped out months ago. But few would argue that Martin's policy positions are responsible for his apparent lock on the position of party leader; even today, very few people know what his positions are on many issues.

By most accounts, the real source of Martin's dominance lies in his control over the internal governance of the Liberal party, as well as his spectacular fundraising (Martin has raised over $6 million to date for his leadership bid). Over the last two years, a well organized campaign has put loyal Martin supporters in charge of most riding associations. Once in control, Martin and his supporters could effectively decide who got to join the party, and when. In many ridings, leadership candidates were only given five membership forms at a time, while Martin supporters were free to bypass this limit. These restrictions were later loosened, but only after Rock, Tobin and others had dropped out of the leadership race (or refrained from joining in the first place).

One Citizen, One Vote: Towards Proportional Representation: An interview with Larry Gordon, Executive Director of Fair Vote Canada, by Susan Thompson

According to Dr. William Cross, the Director of the Canadian Democratic Audit and a professor of Political Science at Mount Allison University, Martin didn't do anything wrong, but simply played by the rules as they exist.

The same rules (or lack thereof) exist for other political parties in Canada as well. Though other parties have not recently experienced the intense and public squabbles over the control of riding associations, their leadership is largely decided by who can sign up the largest number of new members. This in turn is largely determined by who is the most organized and best funded. Few were surprised, then, to see Jack Layton (who had the most funding and signed up thousands of new members) chosen as the leader of the NDP, and Peter Mackay chosen to lead the Progressive Conservatives. Of course, neither MacKay nor Layton were handed the job of Prime Minister upon their election.

Cross argues that "a more democratic system would be to allow all interested and eligible voters to vote for who will be the next Prime Minister." This would involve eliminating the barriers to wide involvement in the leadership election of (at least) the governing party. Instead of an election where only those who have joined before a deadline, paid a fee, and travelled to the (often distant) voting location, Cross advocates what is essentially a US-style primary: all eligible voters would be able to vote for a candidate for Prime Minister.

As it stands, participation rates in leadership selection are very low. Surveys have found that even among supporters of a party, less than 5% participate. Cross cites the election in which Ralph Klein was chosen as the leader of the provincial Conservatives in Alberta as the closest thing to an open leadership contest that has occured in Canada. Voters had to be a member of the provincial party, but they could join at the voting location for a minimal $5 fee. Close to 17% of party supporters turned out for the election, and when the contest went to a second ballot, the number of participants increased.

Asked about the possibility of other parties or groups hijacking a leadership election by mobilizing members to skew the vote a certain way, Cross simply says that there is little evidence of that occuring. On the other hand, the Liberal party spends enough time obsessing about "special interests" hijacking candidate nominations in particular ridings (restrictions placed on distribution of membership forms were justified in this light by the Martin camp) that it's worth asking if the leadership selection process should be more open, not less.

The US-style primary has its own faults, however. South of the border, it is commonly referred to as the "money primary", a reference to the fact that--with very few exceptions--the candidate who raises the most money wins. This, however, would seem to be a question of campaign finance regulation and balanced media coverage. The broader point, according to Cross, is that candidates are forced to appeal to more than a tiny fraction of the electorate. Despite its flaws, the popular election of party leaders (or minimally, Prime Ministers) would at least be successful in moving the focus of leadership campaigns from party power struggles to reaching out to the public at large.

But to Cross, what some have called the "democratic deficit" occurs at a more fundamental level. Elections are considered private events of the Liberal Party, a legal status that means that there is almost no regulation of the process. Spending limits on leadership campaigns, for example, are set and (nominally) enforced by the party. But the enforcement hardly ever comes. It is extremely unlikely, for example, that the Liberal party will deny the leadership to a candidate who goes over internally-set spending limits, and there is no legal recourse--the only option is to appeal to the same riding associations that Martin currently controls. Indeed, it was only with recent legislation on campaign financing (Bill C-24) that leadership candidates are required to fully disclose the sources of funding for intra-party campaigns.

The other democratic short-circuit caused by the private status of political parties is a major concentration of political power in the Prime Minister's office, where, according to Cross, "party members have as much or as little influence on policy as the Prime Minister wants them to have."

One of the less vague planks of Paul Martin's leadership campaign has been to address the "democratic deficit" by giving Members of Parliament more freedom to advance their own views in the House of Commons, and to roll back Chrétien's intensive party discipline in favour of fewer "whipped votes".

Cross says that such measures do little to address the real issues: "that solves the democratic deficit for about 150 Liberal backbench members of Parliament. It's not clear to me that it does anything for the rest of us, because I have no idea what my Liberal candidate thinks about a whole array of policy issues when he or she runs under the Liberal banner, because they don't tell us. They tell us what the Liberal party view is. When they go to Ottawa, you're going to let them vote however they want, but what check does the voter have on that?"

Very little, it would seem. The selection of candidates in federal elections regularly happens with 300 or 400 party members voting, in ridings with over 60,000 voters. Since candidate nomination is often based on mobilization (i.e. which candidate can bus more members to the voting location) rather than policy, candidates have little or no mandate beyond that of the party line.

According to most evidence, Canadian voters overwhelmingly base their choice on the party's leader and platform, rather than individual candidates. As if to confirm this, Prime Minister Chrétien has directly appointed candidates, bypassing the vaguely democratic selection process altogether. In a few instances, "special interest groups" have attempted to use the nomination process to push particular issues, but have been shut out by the Prime Minister's Office. In many instances, "Liberals for Life", a pro-life faction of the Liberal party, attempted to gain nominations, but were shut out by the Prime Minister's Office, which directly appointed its own candidates. When Chrétien chose to directly nominate Art Eggleton in the riding of York Centre, passing over the usual process, veteran city councillor Peter Li Preti sued the Liberal Party to hold the usual nomination process. Because of the Party's effective legal status as a private club, however, he was unsuccessful (though Eggleton was later shuffled out of Cabinet after it was shown that he had given his ex-girlfriend a $36,000 military contract).

Cross argues that this process also needs to be opened up to all eligible and interested voters. If candidate nomination races were infused with ideas or particular policy stands, "you would end up with candidates selected on their own policy programs--these would have to be pretty much in tune with the party, but they wouldn't have to be 100% similar to the Prime Minister's views, and they would then have some legitimacy to challenge the Prime Minister and stake out different positions, and the PMO would have to operate in a very different way than it does now."

Given all of the inward turns the power structure of the Liberal Party has taken, and accepting the Party does not currently appear to be at risk of losing its majority, it is not clear how Canadians can meaningfully participate in the governing of their country. We can vote for the Liberal Party, or against it, but beyond that, things get murky. Anyone who tries to run for nomination as a candidate risks being labelled a "special interest" and being replaced. An appeal to an MP makes little difference, as they have little mandate, and are held in line by the Prime Minister's Office (PMO).

According to surveys conducted for the Democratic Audit, young people are giving political parties a wide berth. Instead, they believe, special interest groups are the most effective way to be represented politically. Furthermore, those in political parties have an average age of 59, are two thirds male, and tended to join when they were younger. For Cross, this raises a deeper issue: "do you want child care policy, or education policy to be made by these people?"

It also seems that the young people surveyed by Cross' colleagues are in some sense right. Participating in policy decisions in a governing party is difficult indeed, as one must convince the party, and then convince the PMO all over again, whereas interest groups can target the PMO directly.

The coincidence of power concentrated in the PMO and declining faith in political parties as a way to get things done raises the spectre of what Canadian philosopher John Ralston Saul calls corporatism. Governments, Saul argues in frequent exhortations to political participation, are the "most powerful force possessed by the individual... [it is] the only organized mechanism that makes possible that level of shared disinterest known as the public good."

When government is run by "interests" and not citizens, says Saul, the public good is swept aside in favour of who can direct the most pressure at politicians. And this is not facilitated by a choice, but rather by a general disenchantment with the system. In The Unconscious Civilization, Saul writes: "Virtually every politician portrayed in film or on television over the last decade has been venal, corrupt, opportunistic, cynical, if not worse. Whether these dramatized images are accurate or exaggerated matters little. The corporatist system wins either way: directly through corruption and indirectly through the damage done to the citizen's respect for the representative system."

Currently, 6 out of every 10 dollars of Liberal campaign financing comes from corporations. Bill C-24, the recent, sweeping campaign finance reform legislation, will ban corporate and union donations to election campaigns and severely limit their donations to leadership campaigns. Such legislation, however, does little to address the fundamental imbalances in the power structure as it currently exists.

Unfortunately, this same structure provides few starting points for individual Canadian citizens who wish to put their "most powerful force" to work, or simply keep it from becoming someone else's most powerful force. At present, a desire to participate in politics is synonymous with frustration for anyone who doesn't have friends in the PMO or the same interests as well-funded lobbyists.

Related articles:

By the same author:

Archived Site

The Dominion is a monthly paper published by an incipient network of independent journalists in Canada. It aims to provide accurate, critical coverage that is accountable to its readers and the subjects it tackles. Taking its name from Canada's official status as both a colony and a colonial force, the Dominion examines politics, culture and daily life with a view to understanding the exercise of power.