DominionSections

Browse Articles

- IndependentMedia.ca

- MostlyWater.org

- Seven Oaks

- BASICS Newsletter

- Siafu

- Briarpatch Magazine

- The Leveller

- Groundwire

- Redwire Magazine

- Canadian Dimension

- CKDU News Collective

- Common Ground

- Shunpiking Magazine

- The Real News

- Our Times

- À babord !

- Blackfly Magazine

- Guerilla News Network

- The Other Side

- The Sunday Independent

- Vive le Canada

- Elements

- ACTivist Magazine

- The Tyee

- TML Daily

- New Socialist

- Relay (Socialist Project)

- Socialist Worker

- Socialist Action

- Rabble.ca

- Straight Goods

- Alternatives Journal

- This Magazine

- Dialogue Magazine

- Orato

- Rebel Youth

- NB Media Co-op

Radio

A Call to Fight Feminicide, in Juarez and Beyond

October 19, 2012

A Call to Fight Feminicide, in Juarez and Beyond

Laval author puts a structural lens on the killings of women and girls

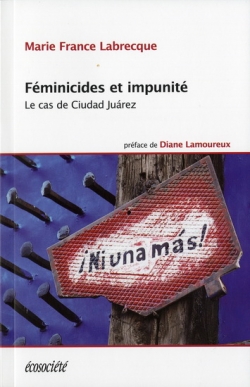

Féminicides et impunité: Le cas de Ciudad Juarez (Feminicide and Impunity: The case of Ciudad Juarez, Les Éditions Écosociété: 2012), by Marie France Labrecque. Photo: Les Éditions Écosociété

Féminicides et impunité: Le cas de Ciudad Juarez (Feminicide and Impunity: The case of Ciudad Juarez, Les Éditions Écosociété: 2012), by Marie France Labrecque. Photo: Les Éditions Écosociété

MONTREAL—Ciudad Juarez. The name conjures up images of violence, maquiladoras, drug traffickers, kidnappings, military interventions, and dead women—too many dead women—in the city's streets.

In her book, Féminicides et impunité: Le cas de Ciudad Juarez (Feminicide and Impunity: The case of Ciudad Juarez, Les Éditions Écosociété: 2012), Marie France Labrecque explores in detail how (and why) women have been special targets, going beyond the usual explanations (organized crime, battles for turf among narco-traffickers, the documented inhumane conditions of maquiladora work, etc.) to relate these deaths to what she calls “feminicides” (féminicides).

Feminicide refers to a system of violence that results from state policies that create social, cultural, economic, and political inequalities and inequities for women and girls. It encompasses more than does the word femicide, the killing, rape, and violence against women and girls because they are women. Making this distinction lets Marie France Labrecque clarify how the ongoing murders of women are embedded in multiple structures of patriarchy found in the family, in society, and in state policies.

Labrecque, a professor emeritus at the University of Laval specializing in Mexico and political economy, argues convincingly that without a deep understanding of feminicide, the political changes needed to end the killings in Ciudad Juarez—and elsewhere—won't be possible. She supports her arguments with quantitative and qualitative data, all horrific and sometimes too much to digest in a single reading.

These details give insights into what needs to be changed to end the murders, punish those who are responsible, and begin to build a more just and equitable society. But they also suggest that making change will not be easy. In fact, women’s rights activists who traveled to Mexico in January 2012 actually found a continuing overall increase in deaths of women and girls since 2006, especially in the border state of Chihuahua where Ciudad Juarez is located, with this happening despite special agencies and programs set up by the Mexican government allegedly to address violence against women.

During the spring presidential election campaign in Mexico, students and others demonstrated against the complicity of the government and its contributions to crime and corruption. Their protests continue, and it is to be hoped that Enrique Peña Nieto, the newly-elected president who begins his term this winter, will listen to their calls and establish the conditions in which full human rights are guaranteed for women and all citizens.

However, it already seems more likely that Peña Nieto's administration will only perpetuate the practices of past governments and do little to end the violence and murders of women. Fears are that he will continue past policies and privilege the militarization of the fight against drug cartels, fail to stop and punish the corruption within the army and police, and do nothing substantive to end the killings of women and girls.

If that is the case, women will remain oppressed and all that Labrecque relates in her powerful book will continue—including the complicity of the USA and Canadian governments in these practices. Therefore, it's important for feminists and others to keep pressing for change and an end to impunity, not only in Ciudad Juarez, but also here in Quebec and Canada where there is need for more and strengthened solidarity with Indigenous women whose lives and rights have not been protected by past and current governments.

The conditions underlying femicide and feminicide are not just over “there”: they are impediments to full justice for all women and girls here, too.

Abby Lippman is a community activist/feminist/researcher-writer in Montreal. An abridged version of this review, translated to French, has been published in aBabord magazine (October/November issue).

Related articles:

By the same author:

Comments

Archived Site

The Dominion is a monthly paper published by an incipient network of independent journalists in Canada. It aims to provide accurate, critical coverage that is accountable to its readers and the subjects it tackles. Taking its name from Canada's official status as both a colony and a colonial force, the Dominion examines politics, culture and daily life with a view to understanding the exercise of power.