DominionSections

Browse Articles

- IndependentMedia.ca

- MostlyWater.org

- Seven Oaks

- BASICS Newsletter

- Siafu

- Briarpatch Magazine

- The Leveller

- Groundwire

- Redwire Magazine

- Canadian Dimension

- CKDU News Collective

- Common Ground

- Shunpiking Magazine

- The Real News

- Our Times

- À babord !

- Blackfly Magazine

- Guerilla News Network

- The Other Side

- The Sunday Independent

- Vive le Canada

- Elements

- ACTivist Magazine

- The Tyee

- TML Daily

- New Socialist

- Relay (Socialist Project)

- Socialist Worker

- Socialist Action

- Rabble.ca

- Straight Goods

- Alternatives Journal

- This Magazine

- Dialogue Magazine

- Orato

- Rebel Youth

- NB Media Co-op

Radio

March Books

March 23, 2009

March Books

New translations by Bolaño and Storm

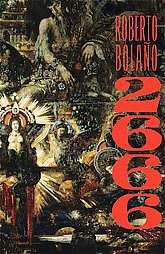

2666

Roberto Bolaño

Translated by Natasha Wimmer

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008

The reception of 2666, Roberto Bolaño’s latest and last novel to be translated into English, has often resembled an exercise in literary myth-making more than literary criticism. Critics have been competing for more lavish adjectives to praise 2666 ever since Bolaño’s other major novel, The Savage Detectives, gained a cult following. Now, just a few months after its release, the discussion has turned away from the novel itself and to the biographical details of the man who wrote it. Bolaño enthusiasts defend his romantic-bohemian image and viciously debate whether he really opposed Chilean President Pinochet, whether he was a drug addict, or whether 2666 was even close to complete when he died almost seven years ago.

So how did a 900-page tome by a formerly obscure Chilean nomad spark a fanatic following with English audiences? Its success has less to do with plot or genre and more to do with Bolaño’s ability to submerge his readers in hundreds of interconnected plots while he borrows from countless genres. To link its disparate parts, the novel has two thematic poles which become entangled by the end. The first narrative link—a reclusive German author who writes under the name Archimboldi—frames the first and last sections of the book. But the major backdrop is Santa Teresa, a fictitious stand-in for Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, and the ongoing mass killings of women there.

Bolaño’s depictions of rape and murder in Mexico go beyond merely graphic. They are painful to read, and that’s exactly the point. Bolaño’s political and moral outrage is expressed by forcing his readers to confront the carnage in its rawest form. There are times when every reader will pause and wonder if Bolaño is perversely enjoying the excuse to spew out lurid details that would make “true crime” fans salivate. After the hundredth continuous page describing the decomposed remains, the coroner’s report, and the known details of another teenaged victim, you’re either shocked, repulsed, or bored.

This boredom is one of Bolaño’s central concerns and it surfaces throughout the novel, starting with the epigraph from Baudelaire: “An oasis of horror in a desert of boredom.” Bolaño doesn’t expound the banality of evil; instead, evil becomes one escape from banality and poverty. Creativity and literature, as embodied by his character Archimboldi, form the alternate sort of escape. Unlike his other books, which obsessively document the creative process, Bolaño rarely details Archimboldi’s motivations as a writer. In one of several indications that 2666 is not quite a finished work, Archimboldi is left as a vague literary silhouette in a world of beauty and boredom where it seems everyone writes books, makes love, or kills people.

Bolaño once wrote: “We never stop reading, although every book comes to an end, just as we never stop living, although death is certain.” The several life stories in 2666 inevitably intersect, drift apart, and get forgotten. To digest each of these stories would require never-ending re-reads. And for Bolaño, now the most acclaimed Latin American author since Gabriel Garcia Marquez, his life and legend seem to be more vital than ever.

—Shane Patrick Murphy

The Rider on the White Horse

Theodor Storm

Translated by James Wright

New York Review of Books Classics, 2009

Theodor Storm's classic novella The Rider on the White Horse contains some meaty pearls of wisdom nestled within a portrait of Germany's sodden Northern Friesland region, but blink and you'll miss them: these flashes of Storm's perceptive strength never take precedence over his evocation of the setting. The land emerges as the focal point for Storm and the novella's characters—a rural community of no-nonsense types who would rather discuss the structural efficacy of their town's protective dykes than allow themselves the sinister distraction of philosophy.

Nevertheless, pearls there are, such as the disturbingly clear sketch of the protagonist Hauke Haien's seething drive to become the town's dykemaster:

Suddenly he felt furiously angry at those faces, and he actually reached out to grasp them, for they obviously wanted nothing better than to block his way to the very position which suited him and only him. These thoughts were never wholly absent from his mind. In such ways, in the living presence of the honor and love in his young heart, ambition and hatred grew up side by side. But they rooted deep inside him, and even Elke failed to suspect their existence.

If the heart of Storm's story offers pastoral beauty and occasional peace (albeit within a community where a catastrophic flood could strike at any time), there is a tension to be felt at its edges: the main tale comes mediated by no fewer than three mysterious narrators, layered one upon the other as the narrative slowly rolls out in the opening pages. We are offered at once a haunting ghost story and the poignant recounting of the life that produced it, a wondrous blend of fantasy and futility that spans over a century and a half and still feels remarkably contained, flanked by the North Sea's frigid depths.

—Robert Kotyk

Related articles:

By the same author:

Comments

Archived Site

The Dominion is a monthly paper published by an incipient network of independent journalists in Canada. It aims to provide accurate, critical coverage that is accountable to its readers and the subjects it tackles. Taking its name from Canada's official status as both a colony and a colonial force, the Dominion examines politics, culture and daily life with a view to understanding the exercise of power.