DominionSections

Browse Articles

- IndependentMedia.ca

- MostlyWater.org

- Seven Oaks

- BASICS Newsletter

- Siafu

- Briarpatch Magazine

- The Leveller

- Groundwire

- Redwire Magazine

- Canadian Dimension

- CKDU News Collective

- Common Ground

- Shunpiking Magazine

- The Real News

- Our Times

- À babord !

- Blackfly Magazine

- Guerilla News Network

- The Other Side

- The Sunday Independent

- Vive le Canada

- Elements

- ACTivist Magazine

- The Tyee

- TML Daily

- New Socialist

- Relay (Socialist Project)

- Socialist Worker

- Socialist Action

- Rabble.ca

- Straight Goods

- Alternatives Journal

- This Magazine

- Dialogue Magazine

- Orato

- Rebel Youth

- NB Media Co-op

Radio

Textbook Treatment

March 20, 2005

Textbook Treatment

State-Sponsored Violence in Pinochet's Chile

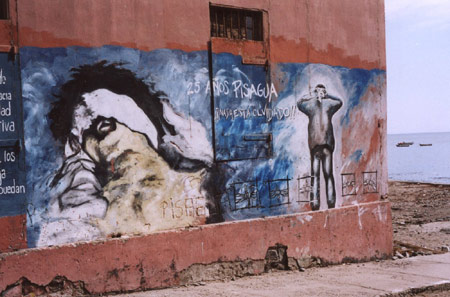

A mural painted in Pisagua, 25 years after the concentration camp was closed. On the left is the torso of an executed prisoner. In the middle: "25 years, Pisagua: Nothing is forgotten!"

IQUIQUE, CHILE--It is easy to become frightened, watching the world around you respond to the world at large. In the suburbs, some flip on the news at 7 for war on Iraq, the tsunami, and the NASDAQ index. Some eat breakfast and drive to work. We move through our days both aware and oblivious. We listen to the news and are affected, but things seem apart. We have our own concerns.

Perhaps a part of our difficulty in responding to injustice today is the too-little of our responses to violence in the past.

On September 11,1973, Augusto Pinochet bombed the government buildings in Santiago, Chile. Salvador Allende, the elected socialist president, was killed inside. The American government and members of the Chilean business community were said to have supported the coup. Allende was known for nationalizing industry and for the long lines in which people would wait for provisions after the economy crashed. He once provided all school children with milk.

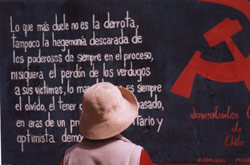

Nadia, reading the mural in Pisagua: "What hurts most in not defeat, nor the shameless hegemony of the powerful ... nor the pardon of the executioners.... The most painful thing, is always when people forget."

The cemetery in Pisagua, where the desert falls into the sea. To the left lies the town. To the right is the site where a mass grave was uncovered in 1990.

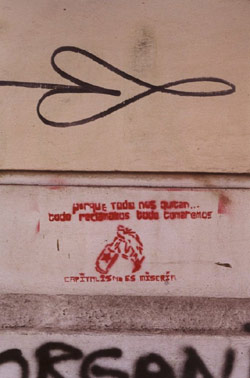

A stencil in Santiago: "Because they take everything from us... we reclaim everything, we take everything. Capitalism is misery."

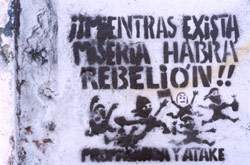

A stencil in Santiago: "As long as there is misery, there will be rebellion."

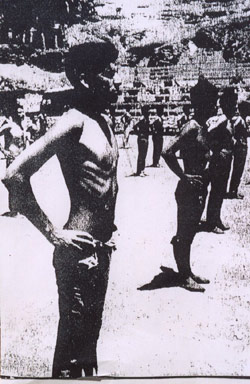

In 1973, a crew of German human rights activists, disguised as military officials, shot a film in Pisagua. Prisoners were asked why they had been detained; most had no answer. The film was shown overseas, fueling pressure to close the camp. For this shot, which appeared in the film, prisoners were made to pose, shirtless, in ranks. (Photographer unknown.)

A mural in Santiago. On the figure's hand is a line from Pablo Neruda: "Even though the footsteps of a thousand years pass over this site, they will not erase the blood of those who fell here."

Pinochet undertook an aggressive campaign to detain or execute those who had been involved in Allende's government or in unions and community organizations. His tactics were both quiet and horrifying. Those who survived have yet to see justice.

As a student in Peace and Conflict Studies at Conrad Grebel University College, in May and June of 2004, I worked with ex-political prisoners in Iquique, Chile. Most had been detained in Pisagua -- a small fishing village in the north. They wanted to create a book of memories that could speak to younger generations.

Our interviews lasted for hours, over tea and bread with plum jam, or shots of Pisco Sour and off-colour jokes. Some took on a fantastical air, and I would wonder which was more important, the real or the believed?

Nadia is a survivor of Pisagua. In 1973, Pinochet's soldiers came for her in the night, leaving her two children alone. She is in her sixties now, sharp featured to her laugh lines. When she passes those who once tortured, in the supermarket, she yells "look what you have done!" and points to the man who begs for money outside. Juan Hervas was beaten so badly that he often doesn't remember his past.

When the soldiers came for Sextor, he jumped from the old trees at the cliff's edge into the river. He hid until nightfall when his uncle came, calling through the fog. Later he stood with hundreds in a cell that reeked of urine and rotten bean gas. He showed the bloodstain on the wall - the place where they shot the man gone crazy from torture - to the people from the Red Cross.

One afternoon, in a lime green office cluttered with pills and patients' files, I spoke with a doctor who had been detained in Pisagua for having studied medicine in Cuba and later refusing to strike against Allende. Our talk moved on from torture under Pinochet to Iraq today and the abuse of those detained there: "This type of torture is not new," he said. "It is textbook treatment. We have known that for years." I asked the doctor what he thought of Pinochet's pending trial and current talk of reparations. He said he thinks that both are important, but that the world will never see real justice if we continue to support an economic system that destroys the environment and abandons the poor. I left his office with a twenty-page letter from him to the Canadian government. It outlined economic and environmental disaster resulting from Canadian mining operations in Chile.

Shortly after speaking with the doctor, I visited Pisagua. I went with Nadia, Lalo (another survivor), and Cesar (a painter and human rights activist). We headed up the cliff behind Iquique, then travelled north across a desert plain. We passed the dusty remains of the salitreras, English-run salt mines, where thousands of Chileans worked for tokens at the company store at the turn of the last century. We dipped into a river valley where bull's-eyes were painted on cliffs across the way - military training. Then the terrain gave way and we descended a slope where the road was broken by fallen debris and ruts in the sand. Below us was Pisagua, where there was a group of fisherman, drinking to Sunday.

First, we went to the theatre where the women were kept in 1973-74. We passed the courtyard where prisoners were made to stand, naked through the night, before their last interrogation. We went to the cemetery where, in 1990, a mass grave was uncovered while military helicopters hovered above. We went to the jail. Images from the interviews came flooding back to me. (The building is now a hotel, shy on business and painted red, with pink trim. In a concrete courtyard outside, a giant puppet of Sponge Bob sits watch above the impoverished village.)

I left Chile via Santiago. From the top of a hill, I could see the black building where Pinochet made his headquarters. I tried to imagine myself working there, or working as a guard at the camps. How do people bring themselves to abuse others? How is a torturer's violence different from that of a society, quietly going about its business while others are denied human rights?

Back in Canada, I still don't understand what happened in Chile, nor can I imagine what the videotapes showing torture, recently released on Chilean news, might mean for survivors.

Our own reporters trudge along. I imagine the news anchors, ironing their jackets and applying make-up carefully, reciting the names of places, reading body counts, and updating the terrorist alert -- all in the same tone of voice. What has made us so accustomed to hearing of horror in a matter-of-fact or distant way? Is this partly why our responses to violence are subdued?

Nadia once told me that she wanted to share her story "so that younger generations will know what a coup really is... so that they will never allow one to occur in the future." I asked how she thought a society numbed by violent television and bland readings of the news might respond to her story. "People may have heard of misery before," she said, "but they have not yet heard about it from me. Don't you think that would be different?"

The courtyard in front of the jail in Pisagua. Spongebob Squarepants sits in the background.

Related articles:

By the same author:

Archived Site

The Dominion is a monthly paper published by an incipient network of independent journalists in Canada. It aims to provide accurate, critical coverage that is accountable to its readers and the subjects it tackles. Taking its name from Canada's official status as both a colony and a colonial force, the Dominion examines politics, culture and daily life with a view to understanding the exercise of power.